After a detailed description of the sail plan for the Swansea Bay pilot boats, Eden Northmore-Jones tells the tale of a spring cruise in ‘Vivian’, with the owner and one of his grooms, named Jack. They set out from Carmarthen, bound for Cork, but revise their course to take shelter in Dale, then visit Solva and St David’s Cathedral on the South Wales coast. They tackle Jack Sound and find the return passage much less of a challenge.

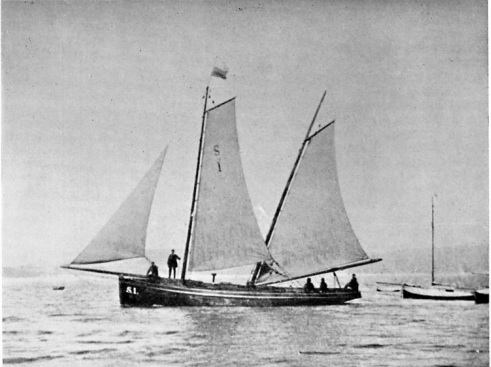

A rig little known, as I believe, but one which there is, in my opinion, none handier, is that peculiar to the Swansea Bay pilot boats. In model not unlike a Penzance lugger they are a species of the genus ‘fore and after’ the foremast is upright, the mainmast rakes aft at an angle of about 65 degrees, they do not carry standing rigging of any description, trawler fashion the jib-outhaul leads under a hook on the stem and serves as a bobstay and the halyards give the masts some support. The mainsail has a ‘bonnet’ which comes off at the second reef, when the boom can be unshipped and a luff-tackle hooked on to the clew for a sheet. There is no fore-boom, as the clew of the foresail comes some way abaft the mainmast, the head of both mainsail and foresails is very narrow, and the gaff is hoisted by one halyard, hooked on about one third its length from the mast. There are no mast hoops, but the sails are laced to the mast, finally there is a jib, and the bowsprit is reefed as a smaller one is set, till the ‘spitfire’ is bent to the stemhead.

These vessels are from ten to sixteen tons YRA measurement, and draw from four to six feet of water. They are celebrated as first rate sea boats, and good sailors on all points except running dead on the mast, when from the great rake of the mainmast the mainsail does not draw well; but they will soak to windward marvellously fast. One of their advantages is that when it comes on to blow, and they are got under main and fore-trysails and storm jib there is no top hamper, and all canvas is inboard; and further as they have only a few inches of bulwarks the decks cannot hold much water.

The ‘Vivian’ is one such as I have endeavoured to describe, of 11 tons YRA measurement, and formerly a Neath pilot, boat. She is owned by P.W.Hughes of ‘ours’, who is well known in the principality as always having a craft ‘as good as she is ugly’ and certainly ‘Vivian’ is no exception to his rule. The build and rig of these craft are decidedly not graceful or handsome; but the vessels are unquestionably serviceable and for a winter cruiser one would have some difficulty in finding ‘Vivian’s equal among vessels her own size.

On Sunday 11 April 1885, she was lying just below the town of Carmarthen, in the tidal river Towey; we were to sail at high water, 4am, the following morning; the crew was to consist of the owner, myself, and a man in the owner’s employ called Jack. This latter is not a good sailor although he has been to sea a good deal with H- in his yachts. By trade he is a groom, and in that capacity he usually serves his master. Jack and I went aboard at 10pm and turned in. H- who is a doctor, spent the night seeing patients; a good preparation for a possible hard days work! Punctually at 4am he roused us out with three thundering good raps on the companion, and ‘now then below there, sleepers ahoy! Eight bells, do you hear the news there?’ We tumbled up, got the canvas on her, slipped the moorings. There was no wind, about north east, so we got out the sweeps to keep steerage way on her and slid rapidly down the ebb tide. At 6am we were off Ferryside, a pretty little place at the north of the river; here we got a faint breeze which freshened slightly as we ran further out of the river so we shipped the sweeps and trimmed sails. By 7.30 we were over the bar and were fairly started on our cruise. The wind soon came out south and we ran across Carmarthen Bay with the trawl down, hoping to get a ‘haul’ before the wind freshened too much; but eight whelks and a two ounce sole were a little disappointing. Before passing to the south of Caldey Island we had the Berthon dinghy aboard and stowed and everything ship-shape; Jack was seriously indisposed with mal de mer; H- was sleeping the sleep he had earned by thirty hours work and I was in charge. It was mid-day before we had anything like a breeze, but when it came there was plenty of it, SW by S.; and I smiled as the vessel lay over and I thought how the cautious H- would start the halyards and haul down the reefs, should he come on deck. About 2 pm as we were bowling merrily by the Saddle Head, a pale pea-green visage slowly emerged from the cabin, and in reply to my remark that it would not be a bad move to pipe to dinner, feebly said it thought ‘the cargo would shift soon’, but I fancy it ‘settled’ again after a spell. Jack however now recovering soon supplied my wants; but the effort caused him once more to collapse. We were bound for Cork, but as it looked like a night at the helm for me, as well as a day I suggested to H- the advisability of running into Milford Haven for the night, that we might all be in good form for the passage across the Channel.

Accordingly I went inside the Crow beacon, off the Linney Head, and stood across Freshwater Bay, west. The others were lying down below. As neither H- nor myself had ever been ashore at Dale, a village at the western extremity of the Haven, we had determined bring up in Dale Roads. Travelling very fast, the vessel crossed the mouth of the Haven and ran right under the high cliffs of St Ann’s; and at 4.30pm the rattle of the patent blocks, as the jib and foresail came down, brought H- and Jack on deck; and in two minutes more the Vivian was at anchor about a cables length from the houses. Whilst we were getting into long-shore ‘duds’, we came to the conclusion that as H- was due home on the following Saturday morning, we had better give up Cork and keep the Welsh coast; we had never seen St David’s cathedral, the shrine to Welshmen dear, or the little harbour of Solva, in St Brides bay, four miles from St Davids; so we decided to make for Solva the next day, and go and overhaul St Davids.

We had a delightful stroll onshore that evening, getting a nice rare view of Skomer and Skokham Islands, the Broad Sound, Jack Sound, and the Hats and Barrels rocks off St David’s Head beyond, from the high ground above Dale. Here too the wild coast, the luxuriant grass, thick, soft, and springy, the rich golden bloom on the furze, and the bluish grey rocks, lit up by the crimson rays of the setting sun, made a natural picture which alone was worth the journey to see. Before returning on board we purchased two crabs of a fisherman, and got from him some sailing directions for entering Solva harbour. An indigestible supper of crabs and whelks, and a smoke after it, did not prevent all hands from sleeping like churches that night, But it may have something to do with no one turning out till 8am next morning. By 8.30 we were underweigh with a nice little breeze about south-west; we soon beat out of the Haven and rounded St Ann’s Head. St Bride’s Bay is formed by St David’s Head on the north-east, and islands of Skokham and Skomer on the south-west. The passage between the two islands is known as the Broad Sound. That between Skomer and the mainland is Jack’s Sound. Through the latter gives the shortest distance from St. Anne’s into St Bride’s Bay, but it is little frequented except by small local coasters, as it bristles with rocks, most of which are dry at low water, and the tide rushes through it a the rate of six or eight miles an hour, forming dangerous eddies and back-washes at the sides and round the rocks; moreover the fairway is not more than a warps length in width.

There is however this advantage to those knowing the locality that ’till an hour after half-tide the current runs through this sound in the opposite direction to the main stream; so that should the tide be foul outside the islands, it is fair through Jack Sound. From St Ann’s Head to the Sound is about three miles, and it is almost the same distance to Skokholm Island, for which we made to have a look at it, and intending to go through Broad Sound. H- had been through Jack Sound once, I had not; it was now two hours flood, so the stream was running at its strongest, and against us, and I half think this helped us change our mind, and determine us to essay the venture. The wind was light south-west the course through Jack sound to Solva is north-east, so it was a dead run. We stood right for Skomer Island to cheat the tide as much as possible. Rapidly we slipped along into a strong eddy, close to the jagged rocks, and so nearly half through the narrow gut. Now a big rock is right ahead; we must leave the friendly eddy and face the torrent; she is goose winged and steered ‘end on.’ Now she gains; now she is stationary; the wind falls light; she goes astern. No — here’s a puff — she goes ahead.

‘Mind your helm’ the mainsail jibes; she slews athwart the stream and is swept back into the eddy, For half an hour are these tactics repeated; the passage is only a cable’s length, but the wind is not enough to beat the rapids. By this time a small smack was close astern bound through; he knew the place, and we were glad to see he tried the same method as ourselves, and with no better success; for some minutes he was close abeam;then came another puff; we began to make headway,the puff held and we were through. When on our way, about two miles across the bay, the smack also succeeded, as the tide by then had slackened. We soon covered the remaining five miles, and by lpm we off Solva. The first thing that strikes one on nearing this little harbour is ‘where is the place?’ a large rock, some quarter mile from the apparently continuous coastline, is the only conspicuous object. On getting close inshore a small inlet is observed completely shut in by high land, and the entrance, which is narrow almost closed by three separate rocks, which stretch in line across it. The way in is on either side of the western rock. ‘Steer bold for the rock,’ the fisherman at Dale had told us, ‘until your bowsprit is just on it, then shift your helm.’

H- went ahead in the Berthon to reconnoitre, I dodged her till he sung out to come on; I let her go right for the rock till ciose to it, then put the helm up and passed it just clear. A cables length straight on, then at right angles to the south-east, and the village is seen up on the steep sideland and two smacks lying in this land locked little lagoon. It is absolutely sheltered from every quarter; the bay outside cannot be seen, it is a perfect little harbour, Solva lies on the north- east side of St Bride’s bay, about six miles in from Ramsay Sound; the houses are invisible from outside; it is a very pretty little spot, quiet and secluded. We landed, and on enquiry, learned that St. David’s was four miles off; that further down the coast to the north-west, in the direction of Ramsey Island, was a little harbour and village called Porth-ly-laish, two miles from St. David’s. as Porth-ly-laish is only five miles from Solva, we at once decided to go there; accordingly we returned on board, weighed anchor and beat out. The wind was now very light, but we reached Porth-ly-laish about 4pm. We found it to be a long, narrow, straight indentation, the land rising up perpedicularly to a great height on each side; a pier had at some period been built, stretching two thirds of the distance across the entrance, but it had now a large breach in it and was otherwise dilapidated. It required but a glance to see that a fearful ‘run’ came in here in heavy weather; the bottom was rough limestone, and it looked as if it would be impossible to get out even with a moderated breeze blowing in. Altogether, it seemed an unsuitable place to stay with a falling barometer, and with little time to.spare H- insisted on leaving at once. We got out the sweeps and pulled out and laid her head once more for Solva. But the wind had fallen very light, the tide was strong against us, and it soon became evident that we should not make Solva before dark.

The evening closed in black and threatening, and by, the time we had got the rock outside Solva under our lee, it was pitch dark. We lowered the foresail, and H- went forward to ‘con’ the vessel, we ran in pretty close. ‘Can you make out the entrance?’ I sung out, ‘No, hard down — let’s get out of this.’ ‘Let me have a look,’ I said and gave H- the helm. But it was no use, I could see nothing but an unbroken black line. So we gave up Solva till daylight, and made up our minds to a night’s ‘dodging’ in the bay. I once asked the skipper of a five-tonner what sort of a sailor his mate was, he replied ‘Oh, he can steer a bit in fine weather’ now this was unfortunately the measure of Jack’s capacity as a helmsman, he could not be trusted to steer at night, so after supper H- took the tiller, and I took a watch below, Jack staying on deck with H-. 4am I was turned.out to take the helm; a fresh north-east wind blowing, colder than any charity I know. They only had the mainsail and No. 2 jib on her, so in reply to H-‘s laconic statement ‘Solva bears N.N.W;,- I don’t know how far’ I said ‘we’ll make sail while the watch is on deck, she must travel for me below if I am to freeze anyhow’ they set the foresail accordingly, then jumped below.

The morning was as dark as the grave. I knew there was no sort of a light anywhere near Solva, but meant to shove her in there in:the earliest possible time, so I let rip to the N.N.W. Were the truth only known I have no doubt most sailors have marvelled at their own imbecility in going to sea — I have often done so; and now as I froze at the tiller, I felt I was acquiring a shocking cold, I decided that the sea was poor as a business, and worse as a pleasure, and I registered a mental vow to stay ashore for ever after. But if unkept good intentions really are paving stones for a warm place, I have supplied that place in with one anyway. At dawn I sighted the rock off Solva, and soon after foresail came down at once more brought the watch on deck, to find the ship in harbour. When I turned out after a snooze I just had a cold, and could hardly speak, but like all ‘shellbacks’ I could ‘growl’. We succeeded in hiring a dog cart and drove to St David’s, there we purchased stores etc., and went to a chemist where H- prescribed for me a mixture of most of the drugs in the shop, in quantity about a pint; I put that in and in about an hour my cold was nearly gone. After inspecting the fine old cathedral, which had just been restored, we walked to St David’s Head, where there is a grand view; and in the evening drove back to Solva. The following morning, Thursday, we sailed at 8am with a fine S.W, breeze, which freshened as the morning wore on. As we crossed St Bride’s Bay, we passed several vessels running in under double reefed canvas, apparently making for Goultrop Roads, an anchorage in the south east part of the bay; seeing this we unlaced the bonnet of the mainsail, which already had one reef in it, and set the fore-trysail and shifted jibs, but nothing came of it and we made sail again.

We returned the way we had come, through the Jack Sound; but this time ‘on tide’ so we ripped through in no time. Nothing of interest occurred till we got up off Stackpole Head; there, seeing we had plenty of time to make Tenby that evening, we determined have a look at Stackpole Quay, a little place under the head. We let go the anchor in the bay, and pulled ashore in the Berthon; but the ‘run’ on the big stones, which form the beach, was too much for the dinghy’s constitution, we thought; so we had to be contented with what we could see lying off. Stackpole Quay is a very queer little dry harbour, terribly exposed to the south-east, where small craft go for limestone; to get in they have to go through a passage only about twelve feet wide, made by clearing the stone away to a depth of about four feet below their natural level, and then run round a sharp angle into the harbour; how they manage it without mishap is a marvel. We weighed anchor about 4pm. And going to the southward of Caldy Island brought up in Tenby Roads as it fell dark. The next morning we sailed for Ferryside, and having hardly any wind at all reached the place about 7pm. The ‘Vivian’ was moored to a ‘pill,’ and left in charge of Jack, H- and I separated, going by train to our respective houses, having thoroughly enjoyed a fine little cruise. I may say I have already reconsidered and rescinded my rash resolution,as a future yarn may shew.

Eden Northmore Jones

The Royal Cruising Club Journal, 1886